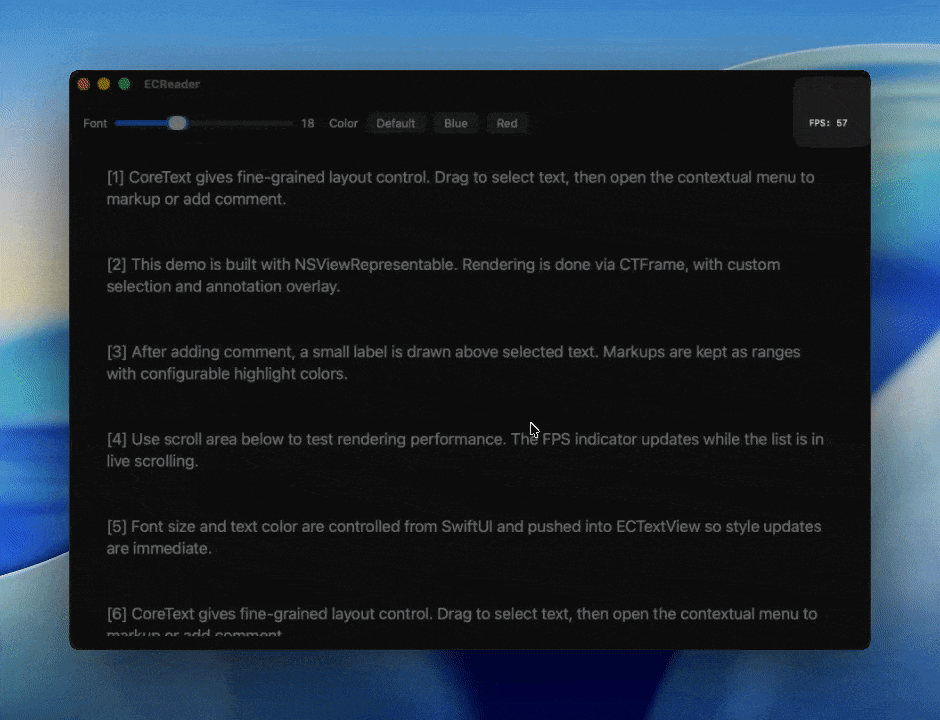

How I Improved CoreText Rendering to 60 FPS

Recently, I started building a video player that uses CoreText to render subtitles. However, when scrolling through the UI, the frame rate dropped to an unacceptable 15 FPS. To fix this, I created a demo that wraps a native text view with CoreText rendering, eventually optimizing the performance to a smooth 60 FPS.